An Introduction

What we now refer to as “La Crosse” occupies the lands of the Hoocąk (Ho-Chunk). The Hoocąk word for the La Crosse area was Hinųkwas.

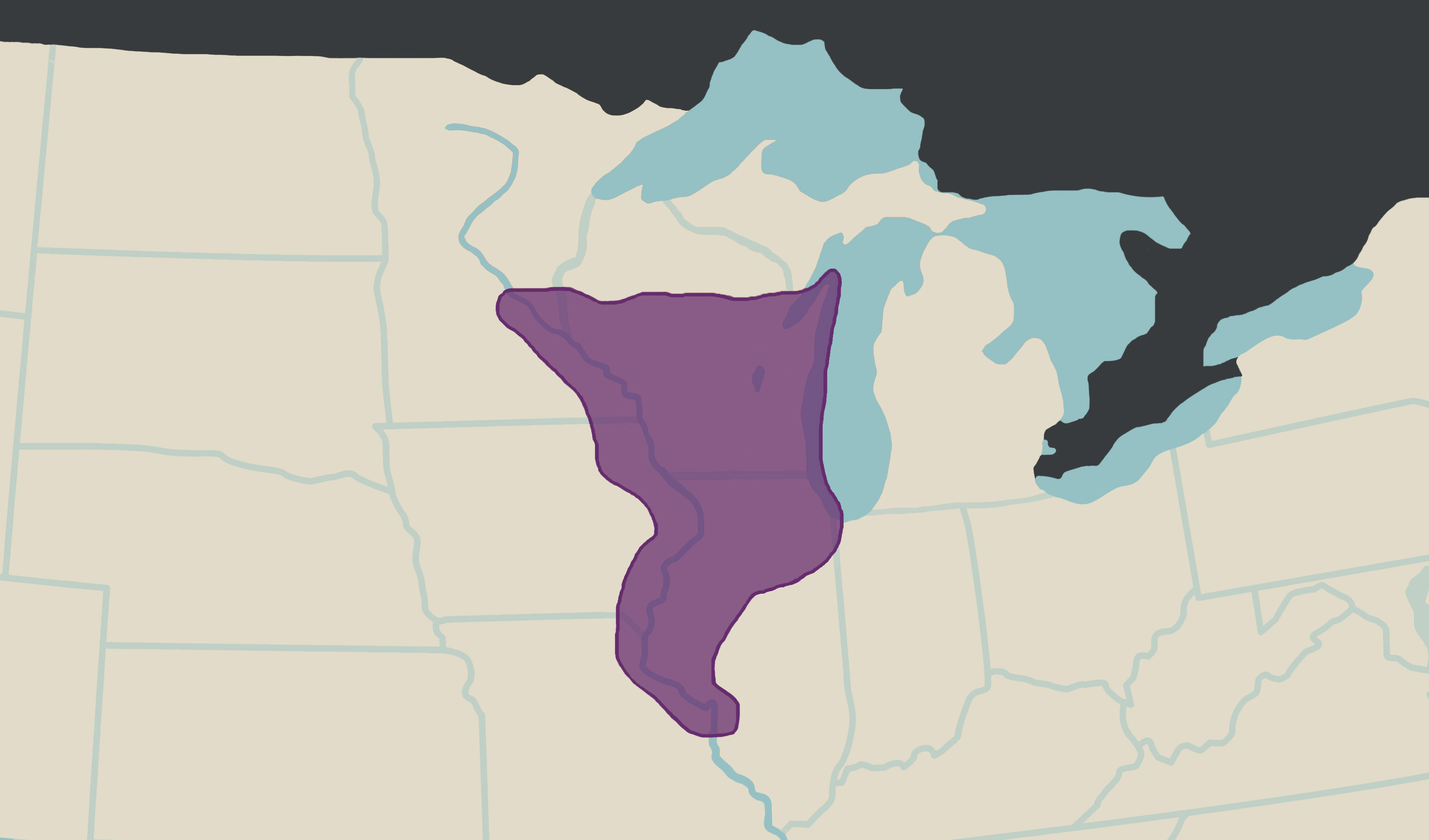

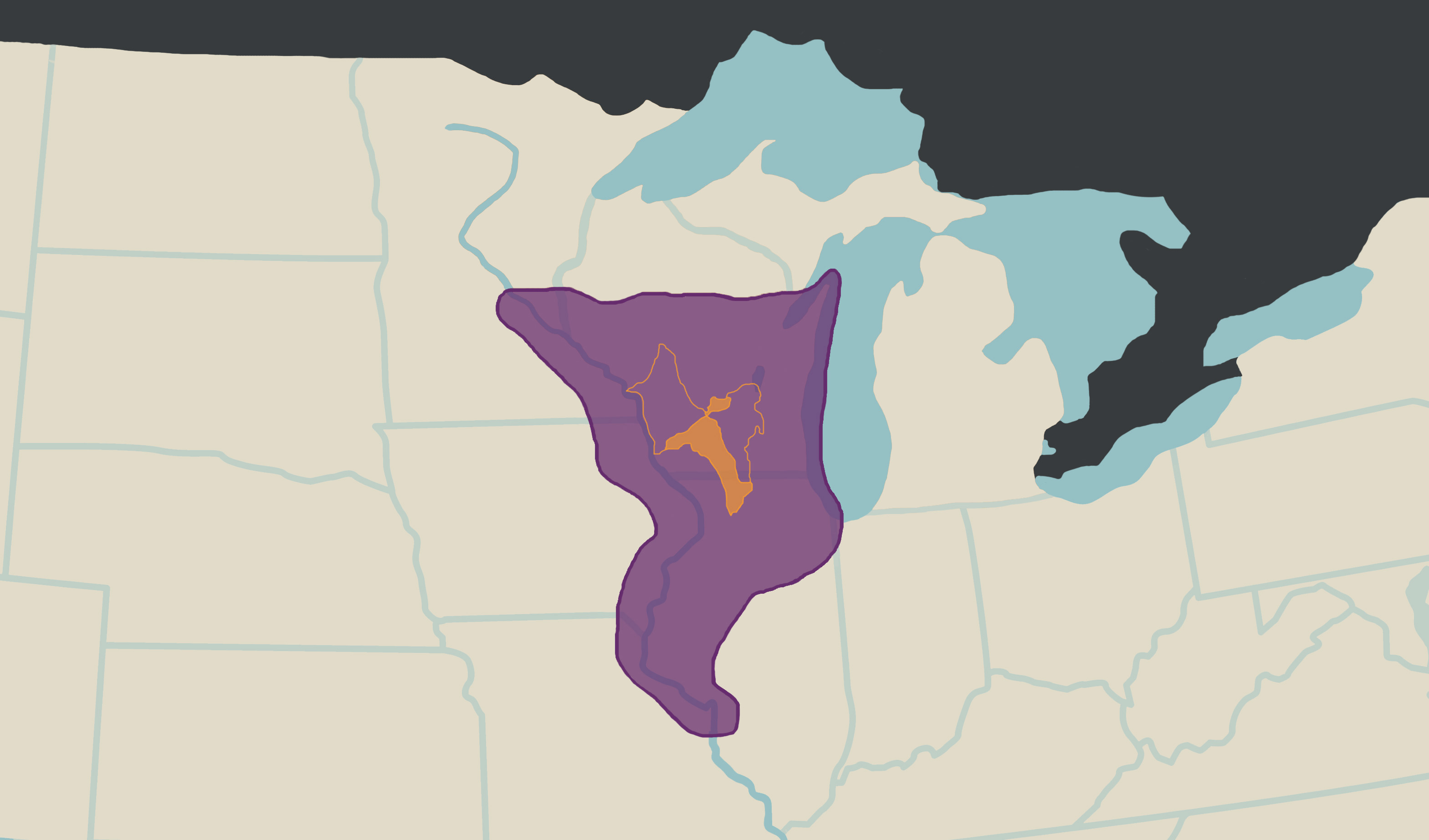

The purple area on this map shows the lands that were stewarded by the Hoocąk for thousands of years before European invasion. While there is no known word for the broad area as a whole, there were many Hoocąk villages scattered across this area, including Hinųkwas.

This timeline reexamines the history that is typically told about La Crosse. Often, Indigenous peoples are talked about in history sources as if they were removed or extinct by the time white colonizers came to Wisconsin. However, Indigenous people live in La Crosse today, and they've lived here since time immemorial.

The Timeline

Please note: the authors of this timeline are forever evolving as learners and educators.

This timeline will evolve to reflect the growth of the authors. Thank you for your understanding.

1825

The treaty of Prairie du Chien was signed.

This was a treaty in which the Hoocąk, Ojibwe, Iowa, Menominee, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Sauk and Fox, and Dakhóta tribes were forced to create borders that described and confined their homelands. Borders were necessary for the U.S. government in order to write land cession treaties with just one tribe—rather than multiple—for specific tracts of land in order to steal Indigenous land at even lower prices.

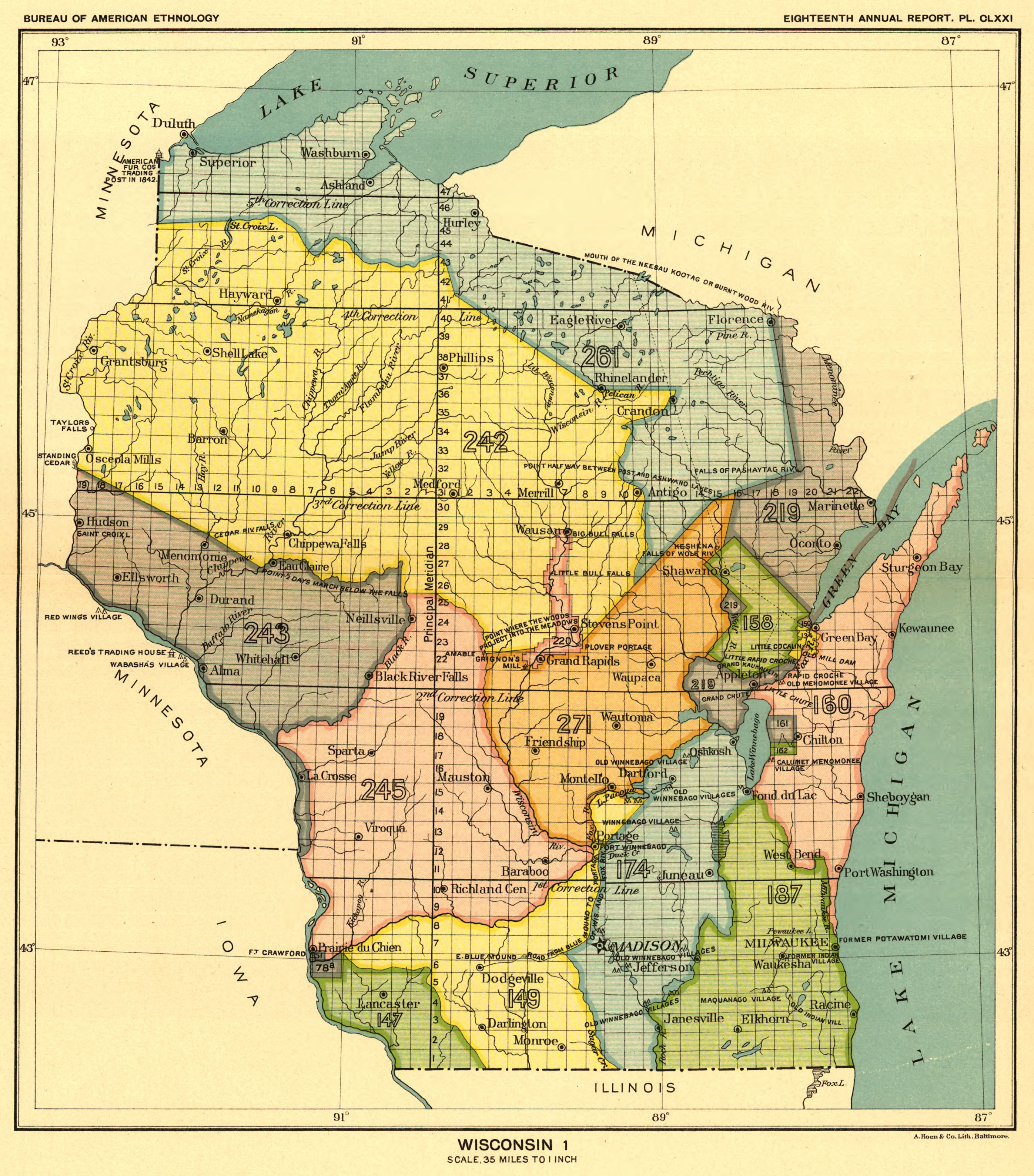

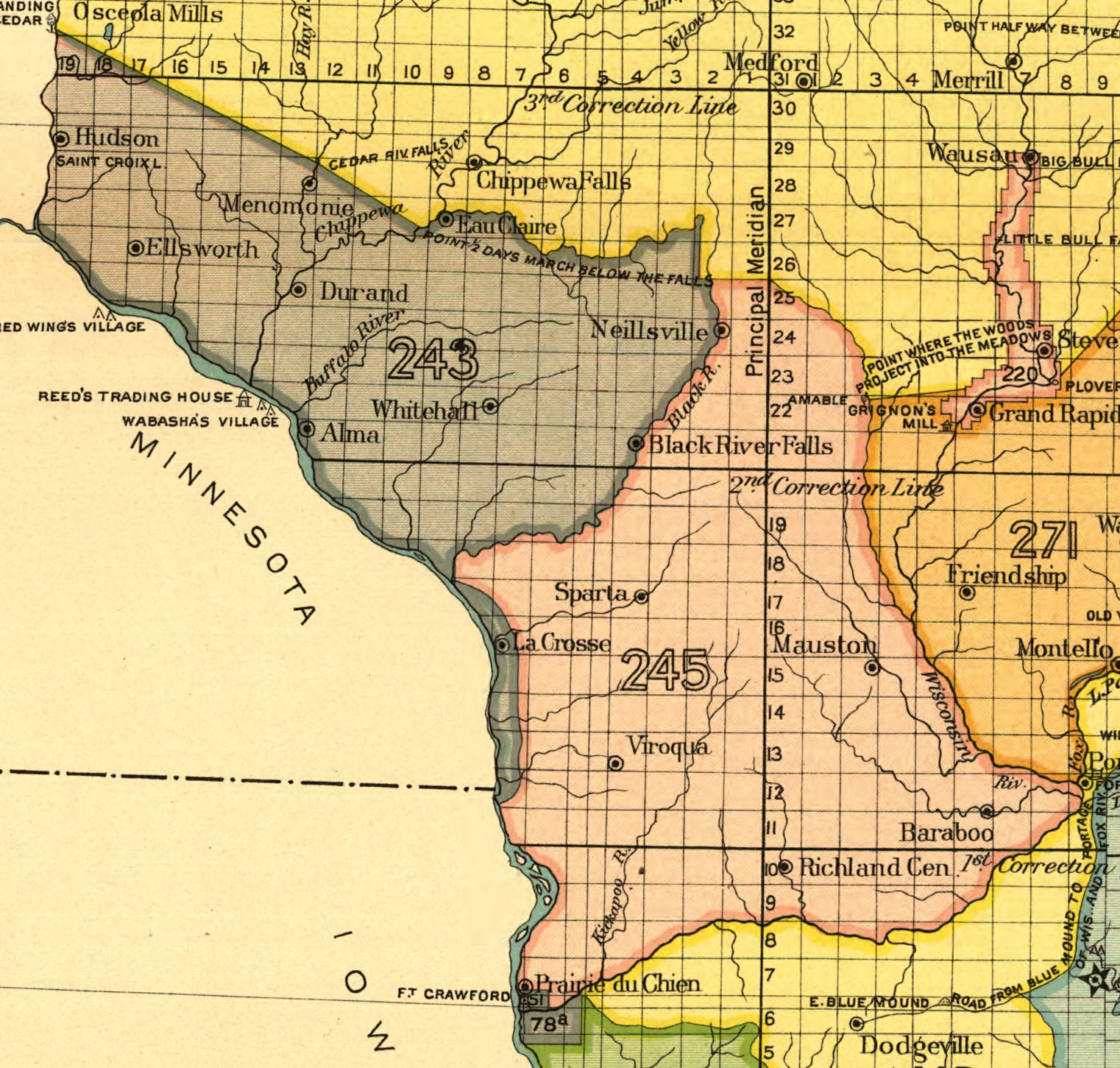

For example, both the Hoocąk and Dakhóta claim Hinųkwas as their homelands because they are related and have both stewarded this land since time immemorial. However, the 1825 treaty forced the Dakhóta to claim this valley between the bluffs, which you can see in this land cession map (right).

1827

The Invasion

By 1827, the tensions between white invaders and the Hoocąk came to a boiling point when two Hoocąk women located north of Prairie du Chien were taken by white men. Learn more about how La Crosse's history is linked the events that led up to the 1829 land cession in this Dark La Crosse Stories episode:

1832

Annuity Census in Portage, WI.

In 1832, there was an annuity census done at the Indian Agency House in Portage, WI, for which Hoocąk families were expected to report all members of their families. Today a historic site, the Historic Indian Agency House recently collaborated with Josie Lee of the Ho-Chunk Nation Museum and Cultural Center to create "A Landscape of Families," an online exhibit, which features a map of Hoocąk villages, and stories of the people who reported to the 1832 census.

1837

Land Cession Treaty with the Dakhóta

As mentioned above, both the Dakhóta and the Hoocąk recognize the land that is today occupied by the city of La Crosse as ancestral homelands. In the 1825 treaty of Prairie du Chien, the Federal Government wanted all land to only be officially reconized by one tribe, so they only had to pay one tribe for a single parcel of land. For reasons unrecorded in primary sources, the Dakhóta claimed the land between the bluffs and the river from what is today Winona, MN to about De Soto, WI. This means that only the Dakhóta were paid for this land. This land cession map of Wisconsin (right) shows these boundaries clearly. In purple is Land Cession 243, which was with the Dakhóta. In pink, just to the east of La Crosse, is the borders of Land Cession 245, which was with the Hoocąk.

The Dakhóta were paid a total of $16,000 for their ceded land in the Wisconsin Territory, which came to $0.18/acre. When this land went on the market just 11 years later in 1848—just weeks after the official, though not true, removal of the Hoocąk from Wisconsin—it was sold by the government for $1.25/acre.

1846

Land Cession Treaty

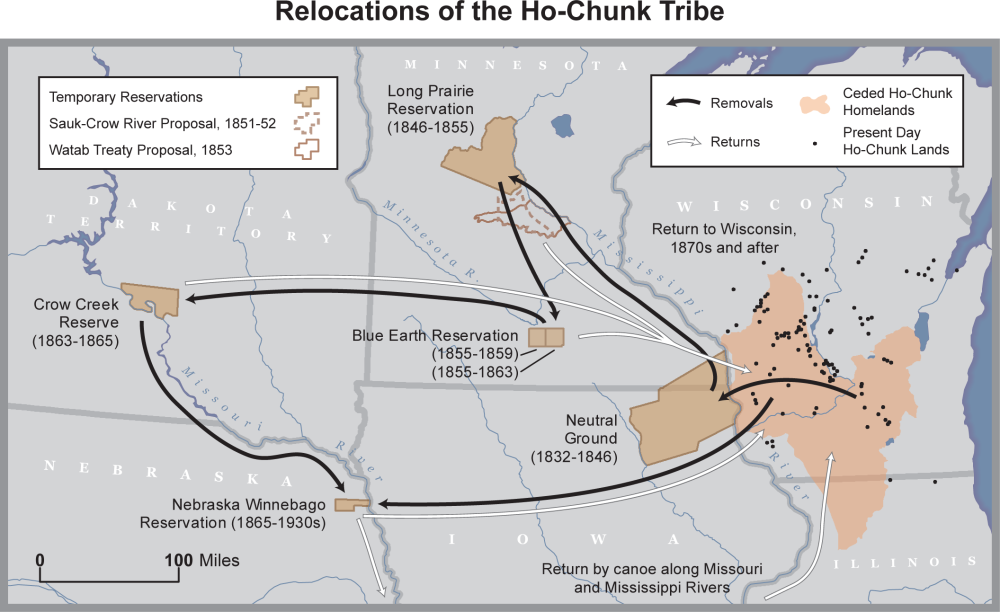

The 1846 land cession treaty sanctioned the removal of the Hoocąk from the Neutral Ground to the Long Prairie Reservation, north of the Twin Cities, MN. However, because so many Hoocąk had travelled back to villages in the Wisconsin Territory, the U.S. government had to finance a large removal effort that would sweep the territory from east to west, forcing Hoocąk people along the way to join them.

Officials rushed to organize these efforts because Wisconsin was to declare statehood in 1848, and all Indigenous peoples not already on reservations needed to be officially removed so towns and farms could be platted for incoming colonizers.

The Army officials hired to conduct the 1848 removal established different rendezvous locations along the Mississippi River to meet up. From there, they forced Hoocąk families onto steamboats and take them up river to the Long Prairie Reservation.

One of these rendezvous locations was a new little rivertown named Prairie La Crosse, made up of just a few dozen families at that point. The public steamboat landing at the time was at the base of State and Front streets, across from Nathan Myrick’s cabin and trading post (today this is the location of Charmant in downtown La Crosse).

The removals were a violent process. In John T. De La Ronde's “Personal Narrative,” (published in the 1876 Wisconsin Historical Collections, Volume VII, page 363), he wrote the following account: “Two old women...came up, throwing themselves on their knees, crying and beseeching Captain Sumner to kill them, that they were old, and would rather die and be buried with their fathers, mothers, and children, than be taken away; and that they were ready to receive their death blows.” Later that same witness saw another group, “on their knees, kissing the ground, and crying very loud, where their relatives were buried.”

Some people jumped off steamboats into the Mississippi River to escape and return home, only to drown, be killed, or captured again. In his memoir (page 18), George C. Nichols, a steamboat pilot who was contracted by the government wrote: “At one time, when a ship load had been collected at La Crosse, and everything was in readiness for taking them aboard, they broke through the place in which they had been confined, and taking their ponies from the adjacent corral, galloped away in all directions.”

1829

Land Cession Treaty

This treaty was forced on the Hoocąk after Waanįk Šuuc (often referred to as “Red Bird”), the leader of the Hinųkwas band, fought to protect his people and their land and resources from invasion.

In this treaty, the lands in what is today south western Wisconsin were ceded (area shaded in orange below):

1832

The Neutral Ground

In 1832, the Hoocąk were removed from Wisconsin and placed in the Neutral Ground, an area in eastern Iowa and southern Minnesota. In the removal map by Cole Sutton above, this section of land is labelled and shaded light brown. The Neutral Ground was established by the U.S. government to put space between the warring Dakhóta and Sauk and Meskwaki tribes. The Hoocąk, peaceful with both groups, were placed in the middle. This was a strategic move on the part of the Federal Government because they wanted white settlers to buy land and colonize the area, and those in power realized the need for the area to appear safe to do so.

The northern-most tip of the Neutral Ground was just across the Mississippi River from La Crosse, in La Crescent, Minnesota. For many Hoocąk, these new borders were easy to disregard and return to their homelands, but others stayed.

Native American Boarding Schools & La Crosse

Wisconsin once had at least fourteen Native American Boarding Schools. Three of these schools largely took Hoocąk children: the Tomah Indian Industrial School, the Bethan Indian Mission (Wittenberg, WI), and the Winnebago Indian Mission School (Neillsville, WI).

Another school tied to La Crosse was the St. Mary's Indian Boarding School, which was in Odanah, Wisconsin on the Bad River Reservation. This school took Ojibwe children away from their parents. It was operated by the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, which is a congregation based in La Crosse. Learn more about this history by watching the below Dark La Crosse Stories episode.