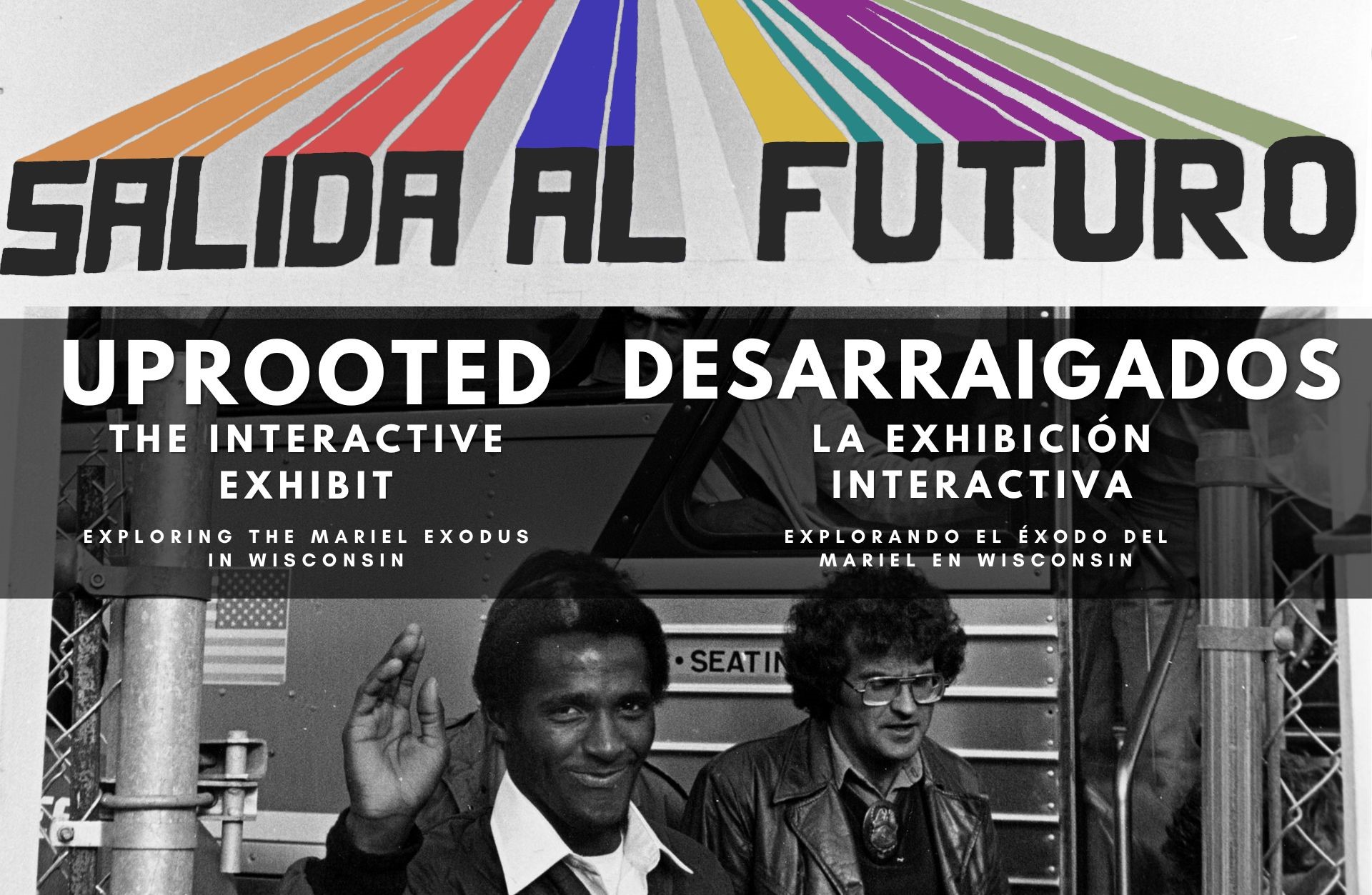

UPROOTED: THE INTERACTIVE EXHIBIT

DESARRAIGADOS: LA EXHIBICIÓN INTERACTIVA

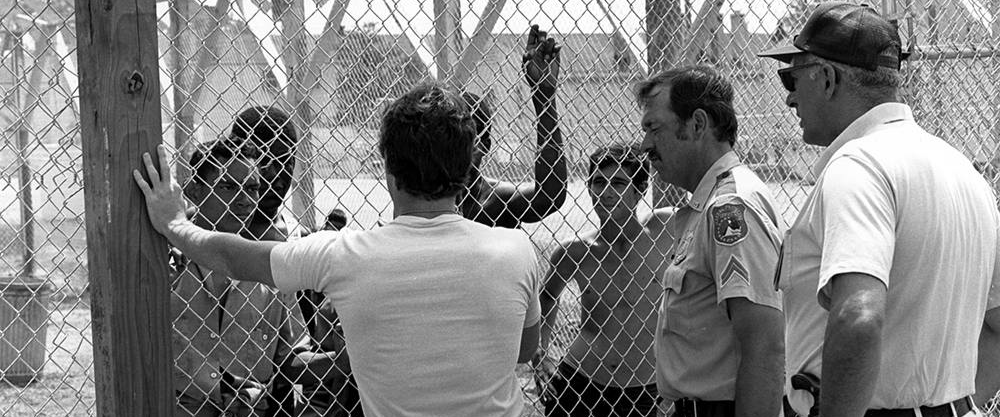

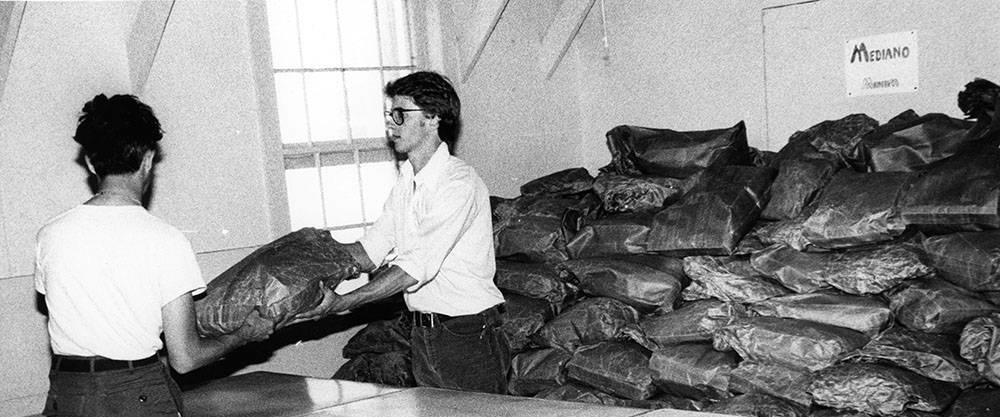

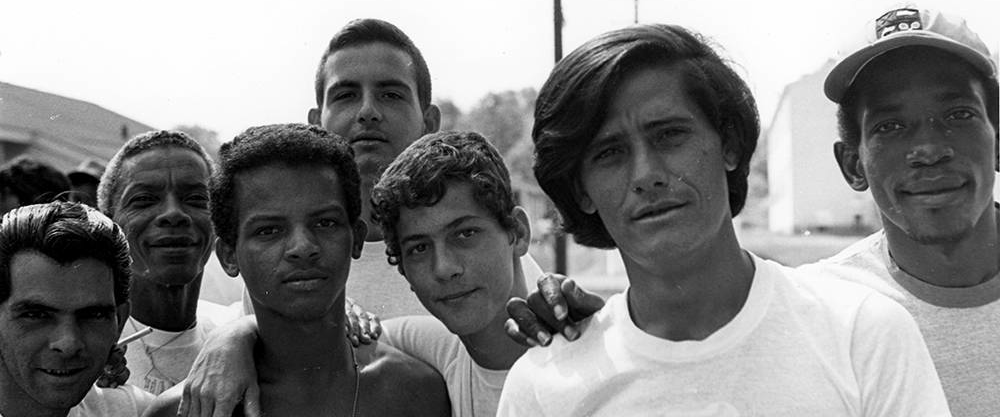

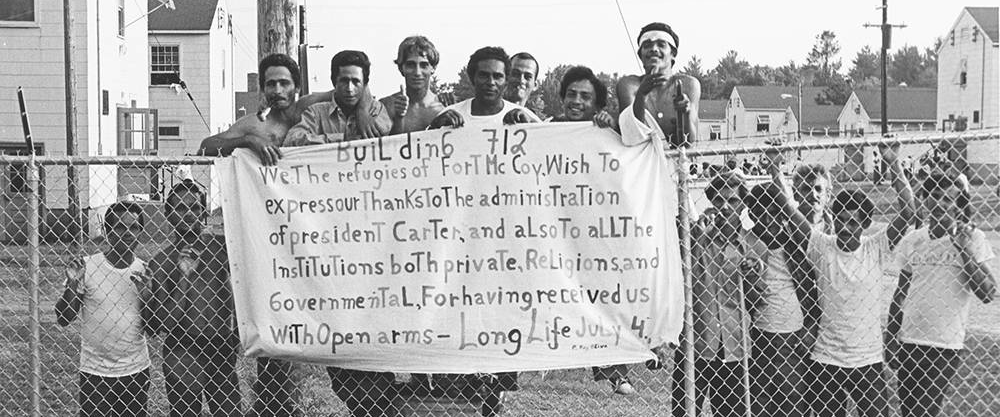

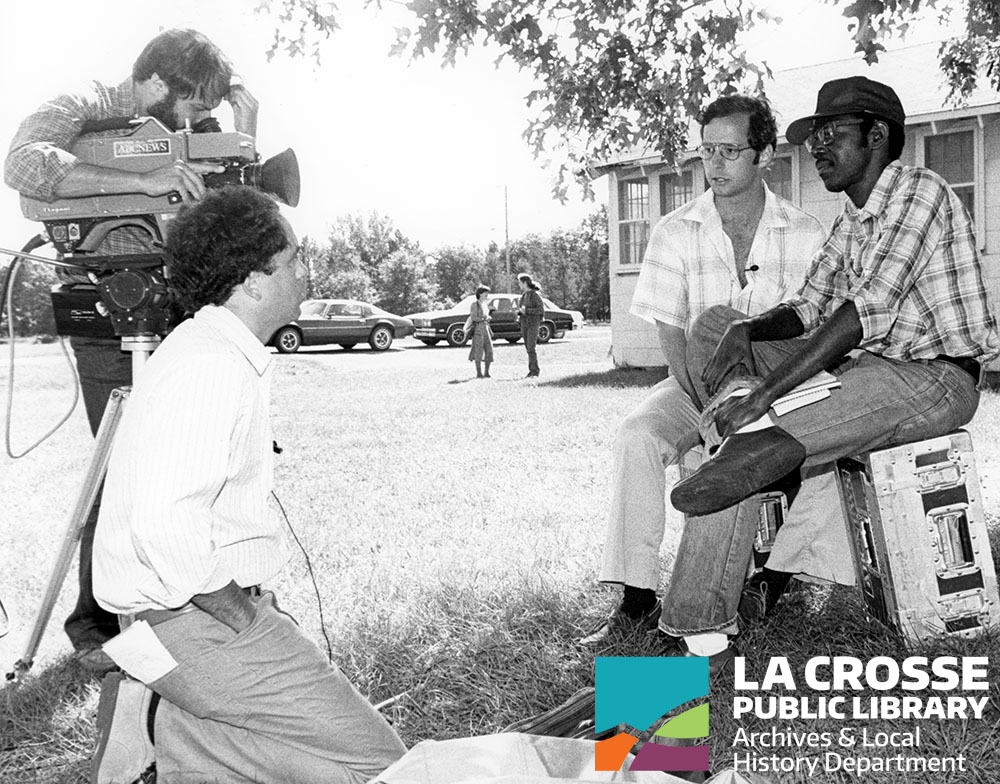

Between April and September of 1980, the military base at Fort McCoy became a refugee compound where over 14,000 Cuban exiles were screened and detained as they awaited potential sponsorship from Wisconsin organizations and families. These men, women, and children had come to Wisconsin as part of the largest exodus in the history of Cold War immigration conflicts between Cuba and the United States, the Mariel Boatlift, which brought a total of 124,769 Cubans to the coast of Florida (almost 1.5 percent of Cuba’s population at the time).

Entre abril y septiembre de 1980, la base militar de Fort McCoy se convirtió en un complejo de refugiados donde se detuvieron y examinaron más de 14000 exiliados cubanos mientras esperaban el patrocinio de organizaciones y familias de Wisconsin. Estos hombres, mujeres y niños llegaron a Wisconsin como parte del éxodo más grande de la historia de los conflictosmigratorios de la Guerra Fría entre Cuba y los Estados Unidos; El éxodo del Mariel, un evento que trajo un total de 124,769 cubanos a las costas de la Florida (casi el 1.5 porciento de la población cubana en aquel momento).

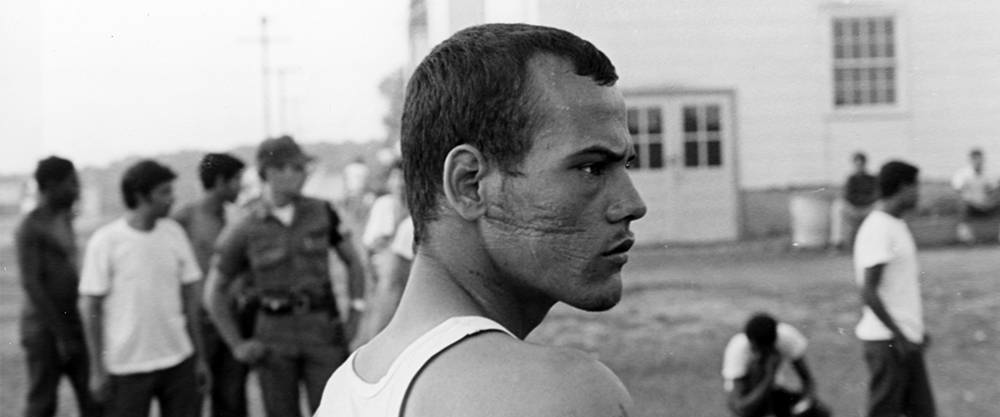

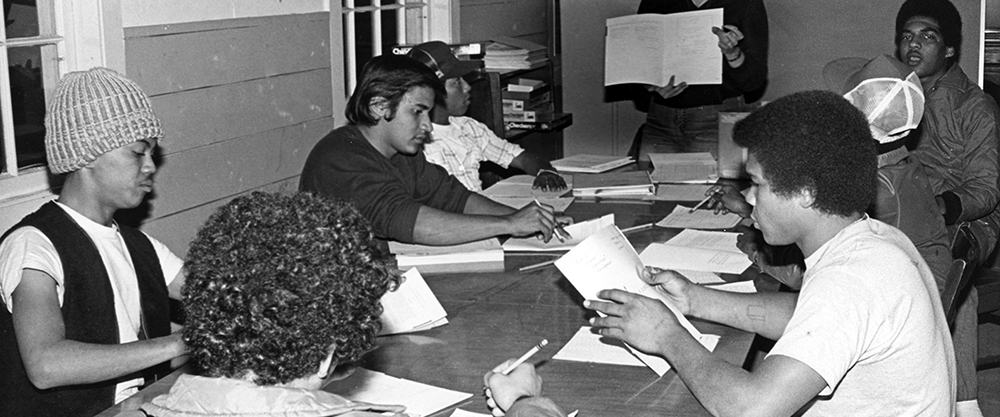

For many of these refugees, the anxiety caused by delayed detention at Fort McCoy, the use of militarization, and the systemic discrimination they experienced clashed with their hopes of wealth and “freedom” in the United States. These experiences also affected their inclusion into small, racially segregated towns such as La Crosse, Sparta and Tomah during the 1980s where predominantly white, non-Spanish speaking majorities dominated the social landscape.

Para muchos de estos refugiados, la ansiedad causada por la demorada detención en Fort McCoy, el uso de la militarización y la discriminación sistémica que vivieron contrastó drásticamente con sus esperanzas de prosperidad y “libertad” en los Estados Unidos. Dichas experiencias también afectaron su inclusión en pueblos pequeños y racialmente segregados durante los años ochenta, como La Crosse, Sparta y Tomah, donde las mayorías blancas angloparlantes dominaban el panorama social.

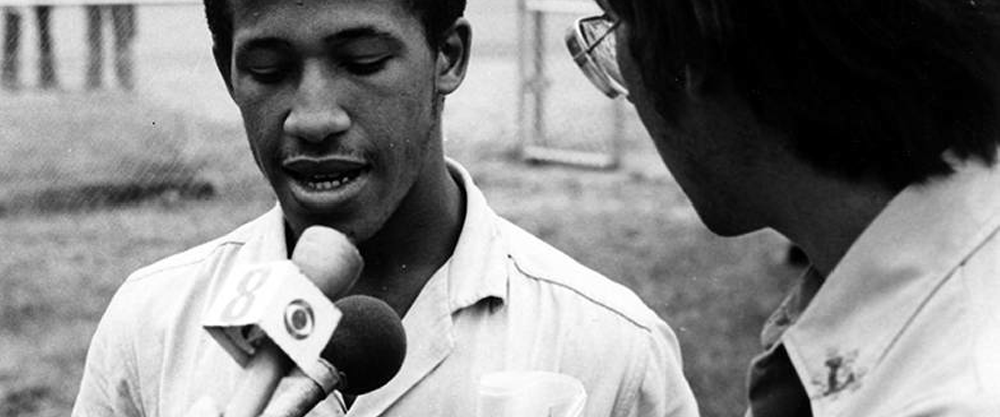

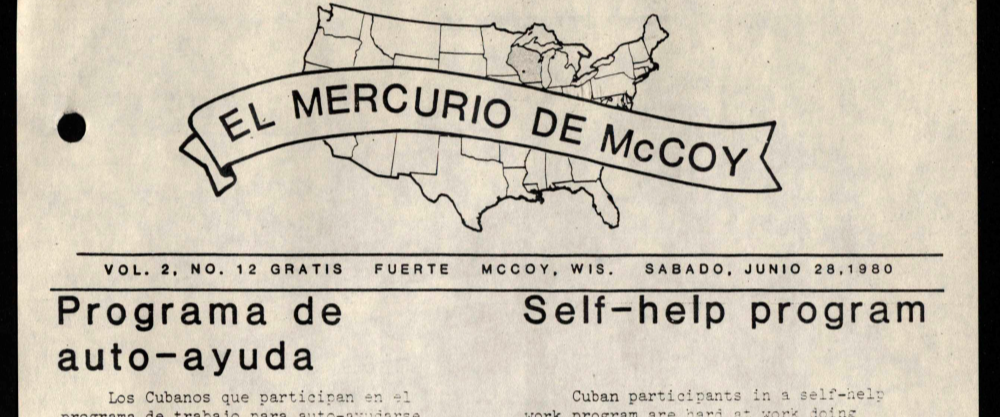

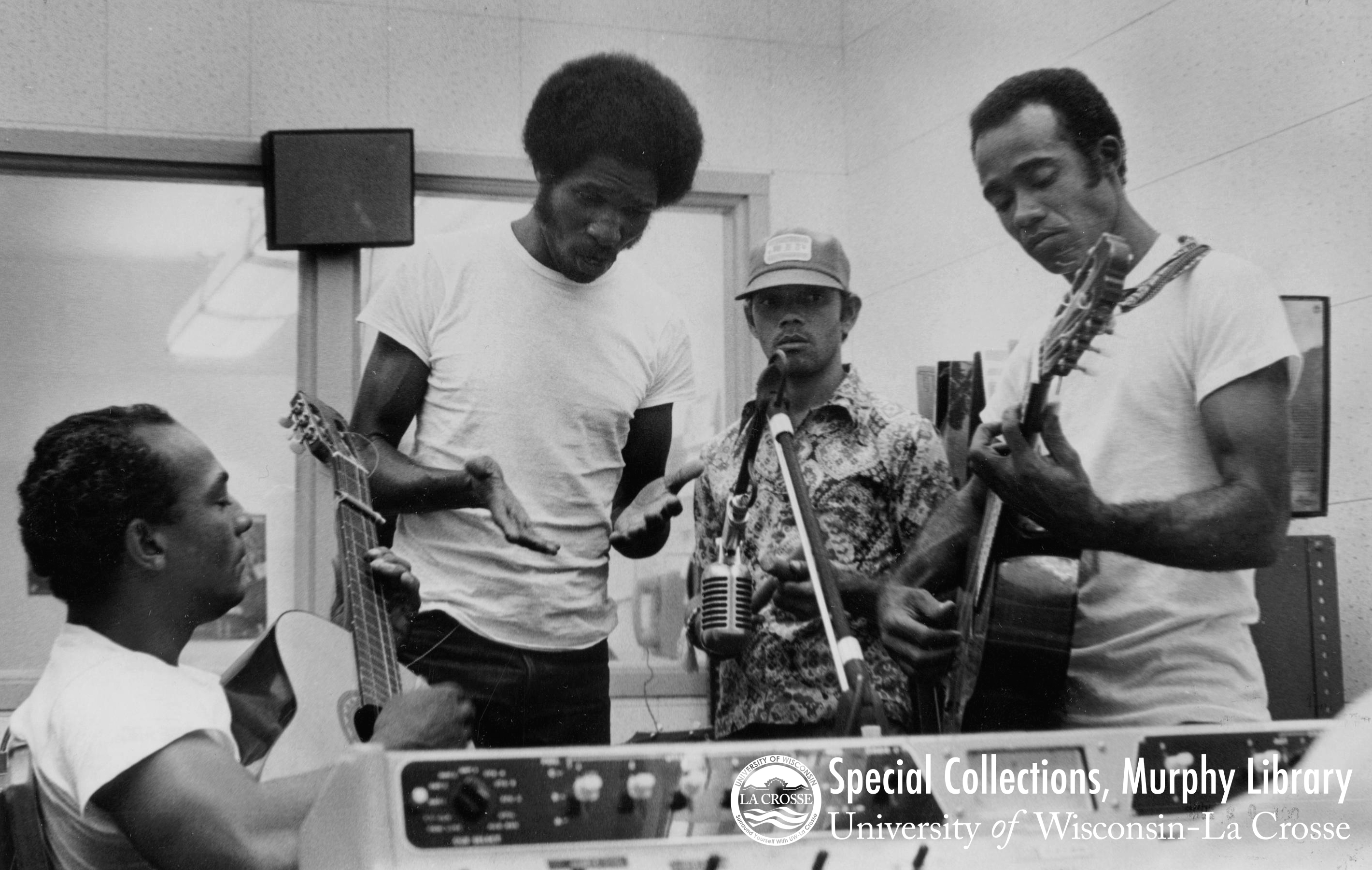

The photographs featured in this exhibit originate from those months at Fort McCoy, exposing the discriminatory social contexts where young migrants were convicted, ostracized, or simply misunderstood. A highlight of this exhibit is a sample of El Mercurio de McCoy, a bilingual publication organized by Cuban refugees inside Fort McCoy. This unique historical resource exposes the cultural frame through which Mariel exiles mourned the cultural loss generated by their displacement and counter the dissemination of the myth of their criminality in 1980s Wisconsin press.

Las fotografías presentadas en esta exhibición provienen de aquellos meses en Fort McCoy exponen los contextos discriminatorios en los que jóvenes inmigrantes fueron condenados, excluidos o simplemente malentendidos. Un aspecto destacado de esta exhibición es una muestra de El Mercurio de McCoy, una publicación bilingüe organizada por los refugiados cubanos en Fort McCoy. Esta valiosa fuente histórica expone hoy el marco cultural desde donde los exiliados del Mariel navegaron la pérdida cultural generada por su desarraigo geográfico, e intentaron contrarrestar la difusión del mito de su criminalidad en la prensa de Wisconsin de los años ochenta.

This exhibit brings these photographs and artifacts primarily as a respectful tribute to the 1980 refugees at Fort McCoy. Our deepest gratitude to Ernesto Rodríguez Ruiz, Rodosvaldo C. Pozo, Marcos A. Calderón-Hernández, Osvaldo Fajardo and the many other Mariel refugees to whom this project is indebted for their courage to remember.

La exhibición muestra estas fotografías y artefactos históricos principalmente como un respetuoso tributo a los refugiados de 1980 en Fort McCoy. Nuestro más profundo agradecimiento a Ernesto Rodríguez Ruiz, Rodosvaldo C. Pozo, Marcos A. Calderón-Hernández, Osvaldo Fajardo, y los otros muchos refugiados del Mariel a quienes este proyecto les está en deuda, por su coraje para recordar.

Throughout the exhibit, episodes from WPR Reports: Uprooted will be displayed as a way to hear more about this history.

This podcast was hosted by producer Maureen McCollum and Dr. Omar Granados, who is the creator of this exhibit. Mariel migrants who live in the La Crosse and Madison areas were interviewed throughout the podcast, so listeners and readers get to hear about their first-hand experiences in their own words.